Is Chronic Inflammation Silently Harming Your Health? Click to do this 60 second test to find out if it is

Childhood Trauma and Chronic Illness in Women

Childhood Trauma and Chronic Illness in Women: The Hidden Link to Chronic Illness, Reproductive, And Mental Health Outcomes

(Article For Health Professionals)

Author: Prem Nand, Clinical Dietitian – Nutritionist, Copyright Maximised Nutrition Limited 2025

Image by Neil Dodhia from Pixabay

Introduction: Childhood Trauma and Women’s Health: Understanding the Hidden Epidemic

Childhood trauma, encompassing emotional, physical, and sexual abuse, neglect, and household dysfunction, is now recognized as a major public health concern with lifelong implications.

The landmark Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACE) study by Felitti et al. (1998) demonstrated a robust dose-response relationship between early trauma and adult chronic disease risk, including cardiovascular, metabolic, autoimmune, and reproductive disorders. For women, the interplay between early trauma and health is particularly complex, with evidence pointing to disruptions in neuroendocrine systems—especially the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) and hypothalamic-pituitary-ovarian (HPO) axes—as key mediators of trauma’s biological imprint.

This article explores the connection between childhood trauma and women's health, with a focus on chronic disease, fertility, pregnancy outcomes, food allergies, and clinical care recommendations.

Summary Table: Health Conditions in Women with Childhood Trauma

How Childhood Trauma Disrupts the HPA and HPO Axes in Women

The Hypothalamic-Pituitary-Adrenal (HPA) Axis

The HPA axis orchestrates the body’s response to stress. In a healthy response, perceived stress activates the hypothalamus, which secretes corticotropin-releasing hormone (CRH), stimulating the pituitary to release adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH), which in turn prompts the adrenal glands to produce cortisol (McEwen, 2007). Cortisol prepares the body to respond to danger, but in chronic stress or early trauma, this axis can become dysregulated—resulting in either hyper- or hypercortisolism.

Women with a history of childhood trauma often exhibit alterations in HPA axis functioning, including flattened diurnal cortisol rhythms, reduced cortisol awakening response, and blunted or exaggerated reactivity to stress (Heim et al., 2000). These disruptions are linked with a wide array of chronic illnesses, including metabolic syndrome, inflammatory diseases, and psychiatric conditions.

The Hypothalamic-Pituitary-Ovarian (HPO) Axis

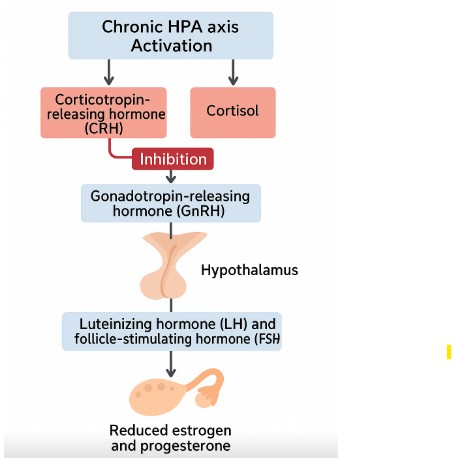

The HPO axis is vital to female reproductive health, regulating the menstrual cycle, ovulation, and sex hormone production. Corticotropin-releasing hormone (CRH) and cortisol (the two hormones produced as part of the stress response) are produced during chronic HPA axis activation and, can inhibit gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH) from the hypothalamus, impairing the release of luteinizing hormone (LH) and follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH) from the pituitary, and ultimately reducing ovarian estrogen and progesterone output (Viau, 2002).

copyright: Maximised Nutrition Ltd

This mechanism explains why women with high ACE scores are more likely to experience menstrual irregularities, anovulation, early menarche, reduced fertility, and polycystic ovarian syndrome (PCOS) (Leeners et al., 2014; Choi & Sikkema, 2016).

Chronic Illnesses Linked to Childhood Trauma in Women

Cardiovascular Disease

Childhood trauma significantly elevates risk for ischemic heart disease, particularly in women. Dong et al. (2004) found that women with high ACE scores had a two- to threefold increased risk of cardiovascular events. Mechanistically, prolonged cortisol elevation leads to hypertension, endothelial dysfunction, and systemic inflammation—contributing to atherosclerosis and myocardial risk.

Autoimmune and Inflammatory Disorders

Trauma-induced dysregulation of immune function has been linked to increased risk of autoimmune diseases such as rheumatoid arthritis, lupus, and multiple sclerosis (Dube et al., 2009). Inflammatory bowel diseases (IBD), including Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis, also show higher prevalence among trauma survivors, mediated by persistent immune activation and altered gut-brain axis signalling (Hobbis & Turpin, 2009).

Gastrointestinal Disorders (IBS/IBD)

Irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) is especially common in women with trauma histories. Approximately 44% of women with IBS report sexual or physical abuse during childhood (Hobbis & Turpin, 2009). The connection is mediated through visceral hypersensitivity, altered gut motility, and microbiome disruption—all of which are modulated by the HPA axis.

Mental Health and PTSD

Trauma is a major risk factor for mood and anxiety disorders. In the National Comorbidity Survey, Kessler et al. (1995) reported that PTSD prevalence in women with trauma histories was over 30%. Depression, generalized anxiety disorder, and dissociation are also more prevalent, especially among those with repeated or complex trauma exposure.

Disordered Eating and Body Image Distortion

Eating disorders—particularly anorexia nervosa, bulimia nervosa, and binge-eating disorder—are significantly associated with childhood abuse and neglect. Brewerton (2007) found that up to 100% of women in clinical eating disorder populations reported childhood trauma. Disordered eating may serve as a coping mechanism or means of exerting control when personal agency has been compromised by trauma.

Maternal Trauma and Intergenerational Transmission of Disease

The Womb as the First Environment

Emerging research demonstrates that the effects of childhood trauma are not confined to the individual but can reverberate across generations. When a woman with a history of trauma becomes pregnant, her altered stress physiology can impact the developing fetus. The intrauterine environment—particularly the hormonal and immune milieu—plays a critical role in fetal programming of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis, brain development, and immune tolerance (O’Connor et al., 2002).

Stress experienced by the pregnant mother, especially if chronic or linked to unresolved trauma, leads to elevated cortisol levels. Although the placenta expresses 11β-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase type 2 (11β-HSD2) to inactivate maternal cortisol, high and prolonged levels can overwhelm this barrier, allowing cortisol to reach the fetal compartment (Glover et al., 2009). This exposure may shape the child's long-term stress responsiveness, emotional regulation, and immune system development.

Impacts on Fetal Brain Development

Prenatal exposure to elevated maternal cortisol has been linked to changes in the fetal brain, particularly in areas such as the amygdala and hippocampus, which govern emotional processing and memory (Buss et al., 2012). These structural and functional changes may predispose the child to emotional dysregulation, anxiety, and depression in later life. Longitudinal studies have also found associations between antenatal maternal anxiety and higher incidence of ADHD and behavioral problems in offspring (Van den Bergh et al., 2005).

Furthermore, maternal trauma and distress can epigenetically modify fetal gene expression. Methylation changes in genes such as NR3C1 (encoding the glucocorticoid receptor) have been found in both mothers and children exposed to prenatal stress, altering HPA axis feedback and increasing vulnerability to stress-related disorders (Hompes et al., 2013).

Maternal Trauma and Childhood Food Allergies

4.1 The Maternal Stress–Allergy Connection Recent evidence links maternal trauma and prenatal stress to allergic sensitization and food allergy development in children.

Wright et al. (2005) demonstrated that high parental stress in infancy is a strong predictor of recurrent wheezing and asthma. Further studies extended these findings to food allergies, showing that maternal anxiety during pregnancy was associated with increased odds of atopic dermatitis and food sensitization by age two (Sausenthaler et al., 2009).

The biological basis for this association may involve several interrelated mechanisms:

• Immune Modulation: Chronic maternal stress alters Th1/Th2 cytokine balance in the fetus, promoting Th2-skewed immunity that favors allergic responses (Hennessy et al., 2009).

• Gut Microbiome: Maternal microbiome changes due to stress can be transmitted during birth and breastfeeding, shaping the infant's gut microbiota and immune tolerance.

• Epigenetic Programming: Stress affects DNA methylation in immune-regulatory genes like FOXP3, critical for T-regulatory cell development (Bromer et al., 2013).

Timing and Severity Matter

The timing of maternal stress appears to be crucial. Antenatal distress during early to mid-gestation—when immune and neurological systems are rapidly developing—has a stronger influence on offspring health outcomes than late pregnancy stress (Glover et al., 2009). Additionally, maternal exposure to multiple traumatic events or chronic stressors (e.g., intimate partner violence, unresolved childhood trauma) magnifies these risks.

Summary of Key Mechanisms Linking Maternal Trauma to Offspring Disease

How Childhood Trauma Affects Fertility and Pregnancy Outcomes

The Impact of Childhood Trauma on Fertility

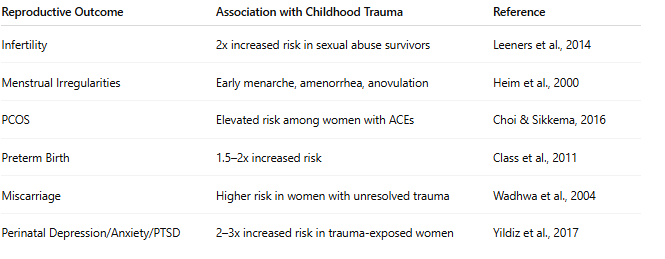

Women with a history of childhood abuse or neglect are significantly more likely to experience infertility or subfertility. A meta-analysis by Leeners et al. (2014) found that survivors of childhood sexual abuse had a twofold increased risk of infertility, even after controlling for confounders such as age, BMI, and socioeconomic status.

Trauma can impair fertility through both psychological and physiological pathways:

• HPO Axis Disruption: As discussed earlier, chronic HPA axis activation suppresses GnRH secretion, reducing FSH and LH, which are essential for ovarian follicle development and ovulation (Viau, 2002).

• Increased Risk of Polycystic Ovary Syndrome (PCOS): Women with ACEs are at increased risk for PCOS, a condition marked by ovulatory dysfunction, hyperandrogenism, and insulin resistance (Choi & Sikkema, 2016).

• Sexual Dysfunction: Trauma survivors may experience pain with intercourse (dyspareunia), vaginismus, and aversion to sexual intimacy, which can complicate attempts to conceive (Leeners et al., 2014).

Reproductive Endocrine Disorders and Menstrual Irregularities

A high ACE score is correlated with earlier menarche, longer time to conception, and irregular menstruation. Exposure to childhood stress can "prime" the neuroendocrine system, leading to a pro-inflammatory state and elevated cortisol levels that inhibit reproductive hormones (Heim et al., 2000). This hormonal dysregulation increases the likelihood of:

• Amenorrhea (absence of menstruation)

• Menorrhagia (heavy menstrual bleeding)

• Anovulation

• Premature ovarian insufficiency (POI)

Women with early trauma also have a higher incidence of endometriosis and fibroids—conditions linked with systemic inflammation and hormonal imbalance (Lukacs et al., 2015).

Pregnancy Complications and Adverse Outcomes

6.1 Preterm Birth, Miscarriage, and Low Birth Weight Childhood trauma has been shown to increase the risk of adverse pregnancy outcomes, including preterm birth, intrauterine growth restriction (IUGR), and miscarriage. Class et al. (2011) found that maternal history of emotional neglect and abuse was linked with a 1.5–2x greater risk of preterm delivery.

Key mechanisms include:

• Elevated Cortisol: Cortisol stimulates placental CRH, which accelerates fetal maturation but may trigger early labor (Wadhwa et al., 2004).

• Inflammation: Trauma-related immune dysregulation may lead to chorioamnionitis or placental insufficiency.

• Behavioral Mediators: Women with trauma histories are more likely to experience poor sleep, substance use, or inadequate prenatal care—all of which can impact pregnancy outcomes.

Increased Risk of Perinatal Mood Disorders

Women with unresolved trauma are at greater risk for antenatal and postnatal depression, anxiety, and postpartum PTSD. These conditions can impair bonding, reduce breastfeeding success, and increase the likelihood of intergenerational trauma transmission (Yildiz et al., 2017).

Clinical Snapshot Regarding Impact of Childhood Trauma on Fertility and Reproductive Health Outcomes

Intergenerational Health Risks

The Role of Maternal Stress in the Rise of Allergic Disease

The sharp increase in pediatric food allergies over the past two decades cannot be explained by genetics alone. Increasing evidence points to prenatal and early-life exposures—especially maternal stress and trauma—as critical environmental modifiers. Research shows that prenatal stress can "train" the fetal immune system toward a Th2-dominant profile, which favors allergic sensitization (Wright et al., 2005).

Key studies reveal:

• Maternal anxiety during pregnancy increases the risk of eczema and food allergies by age 2 (Sausenthaler et al., 2009).

• Elevated maternal cortisol can impair fetal thymus development and reduce regulatory T-cell (Treg) production, which is critical for immune tolerance (Hennessy et al., 2009).

• Stress-induced changes in maternal microbiota (gut and vaginal) alter the microbial inheritance during birth, potentially leading to gut dysbiosis in infants—another known risk factor for allergy (Bromer et al., 2013).

Epigenetic Mechanisms

Methylation and Immune Programming Epigenetics provides the bridge between environment and gene expression. Several studies have shown that early trauma and maternal stress can lead to persistent changes in DNA methylation patterns that influence immune, endocrine, and stress-response systems (Hompes et al., 2013).

Relevant findings include:

• NR3C1 (glucocorticoid receptor gene) hypermethylation in cord blood of neonates born to anxious mothers—associated with altered stress responses.

• FOXP3 methylation linked with lower regulatory T-cell development, associated with food allergies.

• Persistent epigenetic changes in placental genes involved in inflammation, nutrient transfer, and hormone regulation (Monk et al., 2016).

Clinical Application: Trauma-Informed Care in Women’s Health: Why It Matters

Why Trauma Screening Matters

Given the high burden of trauma-related illness in women, clinicians—including GPs, gynecologists, and dietitians—must begin incorporating trauma-informed care into standard practice. Studies suggest that many women with histories of trauma are reluctant to disclose unless asked directly, yet those who are screened compassionately report feeling relief and validation (Seng et al., 2002).

Recommended screening tools include:

• ACE Questionnaire

• PTSD Checklist for DSM-5 (PCL-5)

• Life Events Checklist (LEC)

A trauma-informed approach involves creating a safe, trustworthy clinical space, offering choices and collaboration, and practicing cultural humility. It recognizes that symptoms like pain, fatigue, digestive upset, or menstrual problems may be the long-term echoes of early experiences, not just isolated medical issues.

Integrative Treatment Pathways

Holistic care plans for trauma survivors should address both physical and emotional health, including:

• Nutritional interventions targeting inflammation, blood sugar balance, and hormonal regulation

• Mind-body practices such as meditation, and vagal nerve stimulation

• Psychotherapy, especially trauma-focused modalities like EMDR, somatic experiencing, and cognitive processing therapy

• Medical interventions where needed (e.g., hormonal support, gut restoration, allergy management)

Reference

• Brewerton, T. D. (2007). Eating disorders, trauma, and comorbidity: Focus on PTSD. Eating Disorders, 15(4), 285–304. https://doi.org/10.1080/10640260701454311

• Bromer, C., Marsit, C. J., Armstrong, D. A., Padbury, J. F., & Lester, B. M. (2013). Genetic and epigenetic variation of the glucocorticoid receptor (NR3C1) in placenta and infant neurobehavior. Developmental Psychobiology, 55(7), 673–683. https://doi.org/10.1002/dev.21068

• Buss, C., Davis, E. P., Muftuler, L. T., Head, K., & Sandman, C. A. (2012). High pregnancy anxiety during mid-gestation is associated with decreased gray matter density in 6–9-year-old children. Psychoneuroendocrinology, 35(1), 141–153. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psyneuen.2012.04.019

• Chapman, D. P., Whitfield, C. L., Felitti, V. J., Dube, S. R., Edwards, V. J., & Anda, R. F. (2004). Adverse childhood experiences and the risk of depressive disorders in adulthood. Journal of Affective Disorders, 82(2), 217–225. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2003.12.013

• Choi, K. W., & Sikkema, K. J. (2016). Childhood maltreatment and perinatal mood and anxiety disorders: A review of the literature. Journal of Women's Health, 25(11), 1007–1018. https://doi.org/10.1089/jwh.2015.5460

• Class, Q. A., Lichtenstein, P., Långström, N., D’Onofrio, B. M. (2011). Timing of prenatal maternal exposure to severe life events and adverse pregnancy outcomes: A population study of 2.6 million pregnancies. Psychosomatic Medicine, 73(3), 234–241. https://doi.org/10.1097/PSY.0b013e31820a62ce

• Dong, M., Giles, W. H., Felitti, V. J., Dube, S. R., Williams, J. E., Chapman, D. P., & Anda, R. F. (2004). Insights into causal pathways for ischemic heart disease: Adverse Childhood Experiences Study. Circulation, 110(13), 1761–1766. https://doi.org/10.1161/01.CIR.0000143074.54995.7F

• Dube, S. R., Fairweather, D., Pearson, W. S., Felitti, V. J., Anda, R. F., & Croft, J. B. (2009). Cumulative childhood stress and autoimmune diseases in adults. Psychosomatic Medicine, 71(2), 243–250. https://doi.org/10.1097/PSY.0b013e3181907888

• Glover, V., O’Connor, T. G., & O’Donnell, K. (2009). Prenatal stress and the programming of the HPA axis. Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews, 33(2), 227–236. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neubiorev.2008.10.005

• Heim, C., Newport, D. J., Heit, S., Graham, Y. P., Wilcox, M., Bonsall, R., & Nemeroff, C. B. (2000). Pituitary-adrenal and autonomic responses to stress in women after sexual and physical abuse in childhood. JAMA, 284(5), 592–597. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.284.5.592

• Hennessy, M. B., Deak, T., & Schiml-Webb, P. A. (2009). Early attachment figures and the development of stress responses. Stress, 12(1), 1–14. https://doi.org/10.1080/10253890802044782

• Hobbis, I. C., & Turpin, G. (2009). The role of psychological factors in irritable bowel syndrome. British Journal of Clinical Psychology, 48(3), 307–318. https://doi.org/10.1348/014466508X386358

• Hompes, T., Izzi, B., Gellens, E., Morreels, M., Schrijvers, D., Dom, M., ... & Van den Bergh, B. R. (2013). Investigating the influence of maternal cortisol and emotional state during pregnancy on the DNA methylation status of the glucocorticoid receptor gene (NR3C1) promoter region in cord blood. Journal of Psychiatric Research, 47(7), 880–891. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpsychires.2013.03.009

• Kessler, R. C., Sonnega, A., Bromet, E., Hughes, M., & Nelson, C. B. (1995). Posttraumatic stress disorder in the National Comorbidity Survey. Archives of General Psychiatry, 52(12), 1048–1060. https://doi.org/10.1001/archpsyc.1995.03950240066012

• Leeners, B., Stiller, R., Block, E., Görres, G., & Rath, W. (2014). Consequences of childhood sexual abuse on psychosocial and somatic health: A systematic review. Psychotherapy and Psychosomatics, 83(1), 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1159/000353131

• Lukacs, J. R., et al. (2015). Menstrual irregularity and the biological effects of early trauma: A clinical and evolutionary perspective. American Journal of Human Biology, 27(4), 533–545. https://doi.org/10.1002/ajhb.22683

• Monk, C., Spicer, J., & Champagne, F. A. (2016). Linking prenatal maternal adversity to developmental outcomes in infants: The role of epigenetic pathways. Development and Psychopathology, 24(4), 1361–1376. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0954579412000764

• Sausenthaler, S., Rzehak, P., Schwind, B., et al. (2009). Maternal stress during pregnancy and atopic dermatitis in the offspring. Pediatric Allergy and Immunology, 20(6), 505–511. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1399-3038.2008.00795.

• Seng, J. S., Low, L. K., Sparbel, K. J., & Killion, C. (2002). Abuse-related post-traumatic stress during the childbearing year. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 40(4), 396–406. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1365-2648.2002.02385.x

• Van den Bergh, B. R. H., Mulder, E. J. H., Mennes, M., & Glover, V. (2005). Antenatal maternal anxiety and stress and the neurobehavioral development of the fetus and child: Links and possible mechanisms. A review. Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews, 29(2), 237–258. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neubiorev.2004.10.007

• Viau, V. (2002). Functional cross-talk between the hypothalamic-pituitary-gonadal and -adrenal axes. Journal of Neuroendocrinology, 14(6), 506–513. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1365-2826.2002.00798.x

• Wadhwa, P. D., Sandman, C. A., Porto, M., Dunkel-Schetter, C., & Garite, T. J. (2004). The association between prenatal stress and infant birth weight and gestational age at birth: A prospective investigation. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology, 170(3), 702–708. https://doi.org/10.1016/0002-9378(94)90022-1

• Wright, R. J., et al. (2005). Parental stress as a predictor of wheezing in infancy. American Journal of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine, 171(2), 148–154. https://doi.org/10.1164/rccm.200406-724OC

• Yildiz, P. D., Ayers, S., & Phillips, L. (2017). The prevalence of posttraumatic stress disorder in pregnancy and after birth: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of Affective Disorders, 208, 634–645. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2016.10.009