Is Chronic Inflammation Silently Harming Your Health? Click to do this 60 second test to find out if it is

Long-Term Pain Medication Use in New Zealand

Long-Term Pain Medication Use in New Zealand:

Effects on Health, Gut, and Nutritional Management

Author: Prem Nand, Clinical Dietitian - Nutritionist, NZRD Copyright: Maximised Nutrition Ltd 2025

Introduction

This blog is dedicated to a patient of mine that had serious impact on his health due to long term use of over-the-counter medication (ibuprofen) that resulted in severe chronic renal failure. It got me thinking of what the impact of long term pain medications are.Chronic pain affects approximately 1 in 5 adults in New Zealand, often resulting in decreased quality of life, reduced productivity, and psychological distress. While pharmacological treatments are vital for managing pain, long-term use of pain medications may adversely affect multiple organ systems including the gut, brain, kidneys, and liver.

This article reviews the major types of pain medications used in New Zealand, their long-term health impacts, especially on gut health, and provides evidence-based nutritional strategies to complement or reduce reliance on medication.

Types of Pain Management Medications in New Zealand

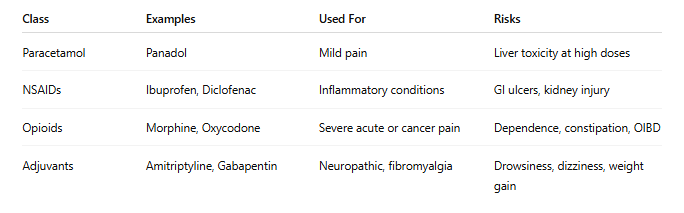

Pain management in New Zealand includes various medication classes tailored to the type and severity of pain:

1. Paracetamol (Acetaminophen)

Paracetamol is a first-line treatment for mild to moderate pain such as headaches or osteoarthritis. Although generally safe, hepatotoxicity may occur with chronic overdose or in patients with liver disease (Yoon et al., 2016).

• Mechanism: Inhibits central prostaglandin synthesis.

• Risk: Liver damage at >4g/day or with alcohol abuse.

2. Non-Steroidal Anti-Inflammatory Drugs (NSAIDs)

NSAIDs like ibuprofen and diclofenac are widely used for inflammatory conditions. They reduce pain and swelling but can impair kidney function, irritate the GI tract, and increase cardiovascular risks with long-term use (Hernández-Díaz & García Rodríguez, 2001; Melgaco et al., 2021).

• Mechanism: COX enzyme inhibition to reduce inflammation.

• Risk: Gastritis, ulcers, renal damage, heart events.

3. Opioids

Prescribed for moderate to severe pain, opioids such as morphine and oxycodone are controlled substances in NZ due to their addictive potential (Volkow et al., 2016). They're reserved for post-operative, cancer, or palliative pain, not recommended for chronic non-cancer pain.

• Mechanism: Binds CNS opioid receptors to block pain signals.

• Risk: Tolerance, dependence, constipation, sedation.

4. Adjuvant Medications

Includes tricyclic antidepressants (amitriptyline) and anticonvulsants (gabapentin, pregabalin) for neuropathic pain (Moore et al., 2014).

• Mechanism: Modulate neurotransmitter reuptake or ion channels.

• Risk: Drowsiness, dizziness, weight gain.

Table 1: Summary of Common Pain Medications

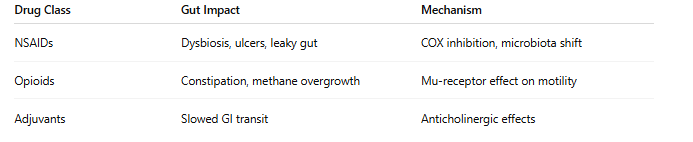

Long-term pain medication use and gut health are closely linked. Several classes, particularly NSAIDs and opioids, can disrupt gut integrity, microbiota, and motility.

1. Disruption of Gut Microbiota

• NSAIDs reduce protective bacteria like Lactobacillus, promote Enterobacteriaceae, and cause dysbiosis (Rogers & Aronoff, 2016).

• Opioids alter motility and microbial fermentation, encouraging constipation and pathogenic growth (Zhang et al., 2019).

2. Increased Intestinal Permeability

NSAIDs inhibit prostaglandin production, reducing mucosal protection and leading to "leaky gut"—a precursor for inflammation, autoimmunity, and metabolic disorders (Bjarnason et al., 1993).

3. Opioid-Induced Bowel Dysfunction (OIBD)

Affects up to 90% of chronic opioid users, causing constipation, bloating, and slowed motility (Camilleri et al., 2020).

4. Gut-Brain Axis Impairment

Changes in microbiota can impact neurotransmitter signaling, worsening cognitive function, mood, and pain sensitivity (Zhang et al., 2019).

Table 2: Gut Effects of Pain Medications

* see below for explanation about COX inhibition and Mu-receptor effects.

Other Long-Term Health Effects

1. Inflammation

Chronic NSAID or opioid use may increase systemic inflammation due to gut barrier disruption and bacterial translocation (Zhang et al., 2019).

2. Metabolic Health

Opioids may impair glucose regulation and increase visceral adiposity (Vuong et al., 2010).

3. Liver and Kidneys

Paracetamol is hepatotoxic at high doses (Yoon et al., 2016), and NSAIDs are linked to kidney damage with long-term use (Melgaco et al., 2021).

4. Brain and Nervous System

Opioids can cause structural changes in brain regions linked to decision-making and emotion, leading to cognitive decline (Younger et al., 2011).

Nutritional Management of Possible Long Term Effects of Pain Medications

1.Management of symptoms

If you have any of the following symptoms:

- chronic fatigue

- renal dysfunction

- gut issues such as constipation, bloating, reflux

- weight gain

- Deranged Liver Function Test

contact a Clinical Dietitian - Nutritionist who has experience working with clients like you (Prem Nand has extensive clinical experience in this area). Also talk to your GP to either get medication review or get a referral to a pain specialist for both medical and pharmaceutical review.

2. Gut-and Body Supportive Nutrition Plan

It is crucial that you get the right gut support. Just being on laxatives may not be useful long term. If you have constipation and are having reflux, going on laxative and omeprazole is not really the best option. You may need to get a SIBO breath test and then work with a Clinical Dietitian - Nutritionist to get a comprehensive gut supportive nutrition plan.

3. Weight & Inflammation Reduction

Weight loss reduces joint stress and systemic inflammation, especially beneficial in arthritis and fibromyalgia (Harvard Health, 2020). But if you have chronic systemic inflammation, it is likely your metabolism is affected (caused by mitochondrial dysfunction). Thus again, working with a Clinical Dietitian - Nutritionist is recommended.

4. Hydration

Important to prevent constipation, particularly in those using opioids or TCAs.

The long-term use of pain medication in New Zealand demands a careful, integrated approach. While pharmacological treatments are essential for pain relief, their long-term side effects—particularly on gut, brain, liver, and kidneys—necessitate monitoring, lifestyle modifications, and nutrition-based support.

A holistic pain management plan incorporating diet, exercise, gut health support, and mental wellbeing can reduce reliance on medications and improve long-term outcomes.

--------------------

Extra Explanations to help you understand some terms:

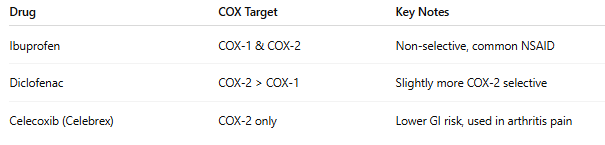

COX Inhibition

COX inhibition refers to the process of blocking the activity of cyclooxygenase (COX) enzymes, which are crucial in the body’s inflammatory response.

There are two main types of COX enzymes:

1. COX-1:

o Found in most tissues.

o Helps protect the stomach lining, supports kidney function, and promotes platelet clotting.

2. COX-2:

o Produced mainly at sites of inflammation.

o Involved in pain, fever, and swelling.

What Happens When COX is Inhibited?

NSAIDs (non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs) like ibuprofen, naproxen, and diclofenac work by inhibiting COX enzymes, reducing the production of prostaglandins—chemical messengers that cause pain, inflammation, and fever.

COX Inhibition = Less Pain, But...

• Inhibiting COX-2 ➝ Reduces pain & inflammation

• Inhibiting COX-1 ➝ Can cause side effects

o Stomach ulcers

o Kidney issues

o Increased bleeding risk

COX Inhibition in Medications:

Mu-receptor effects on molity

The "Mu-receptor effect on motility" refers to how opioid pain medications—which activate mu-opioid receptors—slow down the movement (motility) of the gastrointestinal (GI) tract.

What Are Mu-Opioid Receptors?

• Mu-opioid receptors (MORs) are a type of receptor in the nervous system, especially concentrated in the brain, spinal cord, and GI tract.

• These receptors mediate most of the pain-relieving and side effects of opioids like morphine, codeine, tramadol, and oxycodone.

How Mu-Receptors Affect Gut Motility

When opioids bind to mu-opioid receptors in the GI tract, they:

1. Decrease peristalsis: Slow down the wave-like muscular contractions that move food and stool through the intestines.

2. Increase fluid absorption: This makes the stool harder and more difficult to pass.

3. Cause sphincter dysfunction: Increase tone in the anal sphincter, leading to incomplete evacuation.

Result: These effects lead to opioid-induced bowel dysfunction (OIBD), particularly constipation, bloating, nausea, and gastric stasis.

Clinical Insight:

This is why chronic opioid users are often prescribed laxatives.

Prem Nand's view is that those on long term pain medications should work with an experienced Clinical Dietitian - Nutritionist like herself to look at Nutrition and Lifestyle options for pain management.

References

* Bjarnason, I., Hayllar, J., MacPherson, A. J., & Russell, A. S. (1993). Side effects of NSAIDs on the small and large intestine. Gastroenterology, 104(6), 1832–1847.

* Camilleri, M., Drossman, D. A., Becker, G., Webster, L. R., & Davies, A. N. (2020). Emerging treatments in opioid-induced constipation. Mayo Clinic Proceedings, 95(7), 1366–1381.

* Hawkey, C. J. (2006). COX-2 inhibitors. The Lancet, 367(9521), 1168–1176. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(06)68526-3

* Hernández-Díaz, S., & García Rodríguez, L. A. (2001). NSAID safety: Epidemiologic assessment. The American Journal of Medicine, 110(3), 20S–27S.

* Melgaco, T. L., et al. (2021). Kidney damage from NSAIDs—Myth or reality? Journal of Clinical Pharmacy and Therapeutics, 46(5), 1234–1240.

* Moore, R. A., Derry, S., Aldington, D., et al. (2014). Amitriptyline for neuropathic pain in adults. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, (5).

* Ong, C. K. S., Lirk, P., Tan, C. H., & Seymour, R. A. (2007). An evidence-based update on nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs. Clinical Medicine & Research, 5(1), 19–34. https://doi.org/10.3121/cmr.2007.698

* Ricciotti, E., & FitzGerald, G. A. (2011). Prostaglandins and inflammation. Arteriosclerosis, Thrombosis, and Vascular Biology, 31(5), 986–1000. https://doi.org/10.1161/ATVBAHA.110.207449

* Rogers, M. A. M., & Aronoff, D. M. (2016). NSAIDs and the gut microbiome. Clinical Microbiology and Infection, 22(2), 178.e1–178.e9.

* Volkow, N. D., et al. (2016). Characteristics of opioid prescriptions. JAMA, 305(13), 1299–1301.

* Vuong, C., Van Uum, S. H., et al. (2010). Opioids and endocrine systems. Endocrine Reviews, 31(1), 98–132.

* Yoon, E., et al. (2016). Acetaminophen-induced hepatotoxicity. Journal of Clinical and Translational Hepatology, 4(2), 131–142.

* Younger, J. W., et al. (2011). Opioid analgesics rapidly change the human brain. Pain, 152(8), 1803–1810.

* Zhang, L., et al. (2019). Microbiota-opioid interactions in chronic pain. Frontiers in Microbiology, 10, 139.