Is Chronic Inflammation Silently Harming Your Health? Click to do this 60 second test to find out if it is

THE LINK BETWEEEN STRESS AND WEIGHT

Spore-Forming Probiotics and SIBO: Can They Help Balance the Gut?

By Prem Nand, Clinical Dietitian - Nutritionist, NZRD

Introduction

Spore-forming probiotics are emerging as powerful allies in managing Small Intestinal Bacterial Overgrowth (SIBO) and Intestinal Methanogen Overgrowth (IMO). Unlike conventional probiotics, spore-forming bacteria—mainly from the Bacillus genus—are highly resistant to stomach acid and heat, making them more reliable for gut colonization (Cutting, 2011).

These robust microbes may improve symptoms, restore gut balance, and reduce relapse risk. This article explores the science behind spore-forming probiotics, how they work in SIBO/IMO, and which strains are most effective.

What Are Spore-Forming Probiotics?

Spore-forming probiotics are bacteria that form protective coats called endospores, allowing them to withstand extreme environments. These include the acidic stomach and high temperatures during manufacturing and storage (Cutting, 2011).

Unlike traditional probiotics such as Lactobacillus and Bifidobacterium, which may die before reaching the gut, spore-formers germinate in the small intestine and actively modulate the gut microbiome (Tam et al., 2021).

What Is SIBO and IMO?

• SIBO: A condition where excessive bacteria colonize the small intestine, leading to gas, bloating, abdominal pain, and malabsorption (Rezaie et al., 2020).

• IMO: Driven by methane-producing archaea like Methanobrevibacter smithii, leading to constipation and bloating (Pimentel et al., 2020).

Both conditions are diagnosed using lactulose or glucose breath tests and may co-exist with irritable bowel syndrome (IBS).

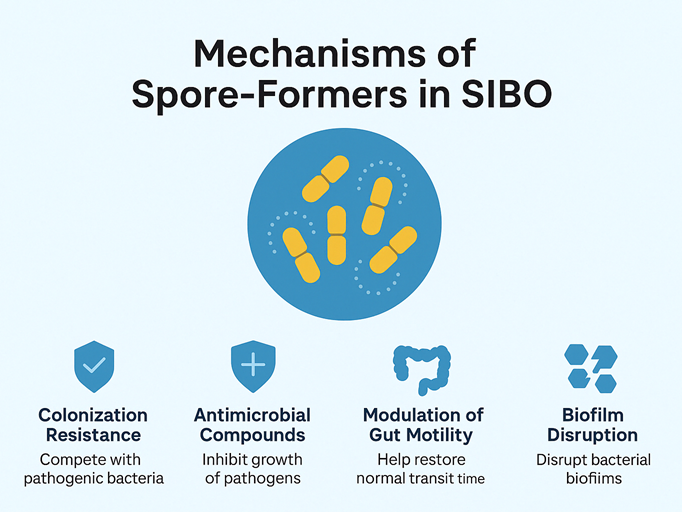

Mechanisms of Action in SIBO and IMO

Spore-forming probiotics benefit gut health in multiple ways:

1. Colonization Resistance

They compete with harmful bacteria and archaea for nutrients and binding sites (Elshaghabee et al., 2017).

2. Antimicrobial Compound Production

Strains like Bacillus subtilis and Bacillus coagulans produce bacteriocins and surfactins that inhibit pathogens (Hong et al., 2005).

3. Gut Motility Modulation

Spore-formers may help improve intestinal transit, countering the slow motility often seen in SIBO/IMO (Sharma et al., 2014).

4. Immune Modulation

They support mucosal immunity and reduce inflammation by stimulating Peyer’s patches (Cartman & La Ragione, 2012).

5. Biofilm Disruption

Spore-formers break down biofilms that protect SIBO-causing microbes from antibiotics (Lopetuso et al., 2020).

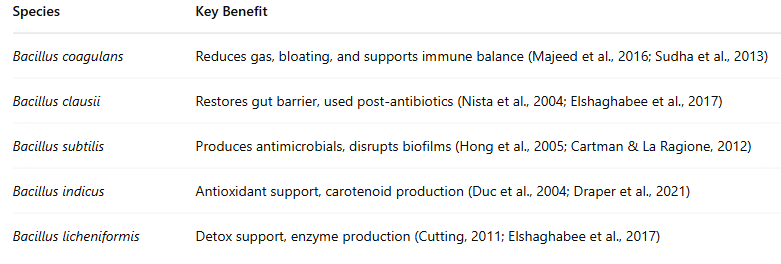

Best Spore-Forming Probiotics for SIBO/IMO

Scientific studies and clinical practice highlight the following strains:

Table 1: Key Benefits of Spore Forming Probiotics

Are They Better Than Regular Probiotics?

Yes. In SIBO and IMO, non-spore probiotics may worsen symptoms by fermenting carbohydrates in the small intestine (Pimentel et al., 2020).

Spore-formers:

• Do not ferment carbohydrates

• Are shelf-stable

• Germinate only where needed (small intestine)

• Don’t require refrigeration (Cutting, 2011)

Clinical Use & Dosing

Most clinical doses range from 2 to 10 billion CFU/day.

Use them:

• Alongside antibiotics (e.g. rifaximin)

• After SIBO eradication to prevent recurrence

• With herbal antimicrobials in functional medicine protocols

Always consult your healthcare provider for personalized dosing, especially in immunocompromised individuals (Snydman, 2008).

Are They Safe?

Generally yes. However, caution is advised in:

• Patients with suppressed immunity

• Individuals with central lines

Ensure your probiotic is third-party tested and free of harmful strains like Bacillus cereus (Snydman, 2008).

Conclusion

Spore-forming probiotics represent a scientifically supported, gut-targeted approach to managing SIBO and IMO. With antimicrobial, anti-inflammatory, and gut-motility benefits, they address both symptoms and root causes.

Incorporating strains like Bacillus coagulants and Bacillus subtilis can enhance the success of SIBO treatment protocols—especially when used strategically alongside diet, antibiotics, or herbal antimicrobials.

CTA (Call-to-Action)

👉 Looking for gut-healing support? Speak to me today: book a 15 minute discovery phone call where I can briefly review and advise if coming for a full consultation is appropriate - Prem Nand, Clinical Dietitian-Nutritionist, NZRD

References

Cartman, S. T., & La Ragione, R. M. (2012). Bacillus subtilis spores: a novel oral vaccine delivery system. Microbial Cell Factories, 11(1), 1-7.

Cutting, S. M. (2011). Bacillus probiotics. Food Microbiology, 28(2), 214–220.

Draper, L. A., Ryan, F. J., Dedi, C., & Ross, R. P. (2021). Probiotics and gastrointestinal disorders. Current Opinion in Gastroenterology, 37(1), 3–10.

Duc, L. H., Hong, H. A., Barbosa, T. M., Henriques, A. O., & Cutting, S. M. (2004). Characterization of Bacillus probiotics available for human use. Applied and Environmental Microbiology, 70(4), 2161–2171.

Elshaghabee, F. M. F., Rokana, N., Gulhane, R. D., Sharma, C., & Panwar, H. (2017). Bacillus as potential probiotics: status, concerns, and future perspectives. Frontiers in Microbiology, 8, 1490.

Hong, H. A., Duc, L. H., & Cutting, S. M. (2005). The use of bacterial spore formers as probiotics. FEMS Microbiology Reviews, 29(4), 813–835.

Khanna, S., & Tosh, P. K. (2014). A clinician’s primer on the role of the microbiome in human health and disease. Mayo Clinic Proceedings, 89(1), 107–114.

Lopetuso, L. R., et al. (2020). Biofilm disruption and intestinal microbiota modulation as new therapeutic strategies in SIBO. World Journal of Gastroenterology, 26(33), 5000–5014.

Majeed, M., Nagabhushanam, K., Arumugam, S., Beede, K., & Majeed, S. (2016). Evaluation of the probiotic strain Bacillus coagulans MTCC 5856 in the treatment of diarrhea-predominant irritable bowel syndrome. PeerJ, 4, e1804.

Nista, E. C., Candelli, M., Zocco, M. A., Marzetti, G., Cammarota, G., Gasbarrini, G., & Gasbarrini, A. (2004). Bacillus clausii therapy to reduce side-effects of anti-Helicobacter pylori treatment. World Journal of Gastroenterology, 10(4), 555.

Pimentel, M., Mathur, R., & Chang, C. (2020). Methanogens in human health and disease. American Journal of Gastroenterology, 115(8), 1132–1140.

Rezaie, A., Buresi, M., Lembo, A., Lin, H., McCallum, R., Rao, S., ... & Pimentel, M. (2020). Hydrogen and methane-based breath testing in gastrointestinal disorders: The North American consensus. American Journal of Gastroenterology, 115(11), 1751–1760.

Sharma, A., Rao, K., Santhosh, S., & Nanda, R. (2014). Spore-forming probiotics: Bacillus species. Journal of Pure and Applied Microbiology, 8(1), 239–250.

Snydman, D. R. (2008). The safety of probiotics. Clinical Infectious Diseases, 46(Supplement_2), S104–S111.

Sudha, M. R., Yelikar, K. A., & Madempudi, R. S. (2013). Probiotic Bacillus coagulans unique IS2 in treatment of patients with bacterial vaginosis: a pilot study. European Journal of Obstetrics & Gynecology and Reproductive Biology, 170(2), 439–441.

Tam, N. K. M., Uyen, N. Q., Hong, H. A., Duc, L. H., Hoa, T. T., Serra, C. R., ... & Cutting, S. M. (2021). The intestinal life cycle of Bacillus subtilis and close relatives. Journal of Bacteriology, 193(18), 4524–4538.